Where’s Andy?

by Charlie Vascellaro

It was just another day for the workers at the cemetery. They weren’t particularly gentle about lowering my friend Andy Rubin into his grave. There was something unsentimental and matter-of-fact about it. Like it was just the next thing on their to-do list before the end of the day. I suppose when you do it for a living it might look that way.

Four of them wheeled his coffin on a gurney into position, slipped some straps underneath and passed them to each other. As they were getting ready to lift the coffin, I thought about tapping the worker closest to me on the shoulder and asking if I could cut in. Watching four strangers lower my buddy into his final resting place seemed so impersonal. I looked around at the friends and loved ones nearby and thought, “Shouldn’t four of us be doing this?”

They plopped him into the snug rectangular hole with a thud and stepped away taking the gurney with them.

It looked claustrophobic down there. You start to comprehend the gravity of the expression “six-feet-under” when you see the box containing your friend dropped into the cold, cold ground.

Andy’s immediate family was called first to begin scooping the piled-up dirt into the grave. In accordance with Jewish tradition, we were told to use the back of the shovel first as an expression of reluctance to the task at hand. Then we were told to turn it over to get a full scoop. When that first scoop, administered by Andy’s mother, hit the top of the wooden coffin it sounded like a drum echoing in the dell.

I knew then against all my hopes that Andy wasn’t going to pop up like a Jack-in-the Box and say, “Ta Da!” I was not alone in this. Several of us expressed the expectation that Andy would show up late for all the day’s scheduled events just like always. As the burial ceremony was coming to an end the cemetery workers began shoveling in the rest of the dirt, I tossed in a can of Andy’s favorite “Sweet Baby Jesus” beer and a 1975 Tom Seaver Topps baseball card.

Before his burial, we attended Andy’s funeral at the Plaza Jewish Community Chapel, on Amsterdam Avenue in the Upper West Side neighborhood where he grew up and partially resided in the same apartment where his mother still lives. When I arrived in the neighborhood, I looked for Andy around every corner.

Sometimes we’d meet at Andy’s favorite Irish Pub, McCoy’s, just a few blocks from his family apartment. Sometimes at the New Yorker Hotel where I usually stay when I’m in town on 34th Street and 8th Avenue near Penn Station. Sometimes we’d meet at one of the bars in Penn Station or the Big Apple in front of Citi Field when going to Mets games.

Andy was stubborn in his insistence of taking the No. 7 Subway train to the games while I prefer riding the Long Island Railroad from Penn Station. When we didn’t ride together, we’d meet in front of the apple. This past season, we caught a handful of games together there and even more on the television at Standings, a favorite East Village bar of Andy’s. We became regulars together and separately.

-o-

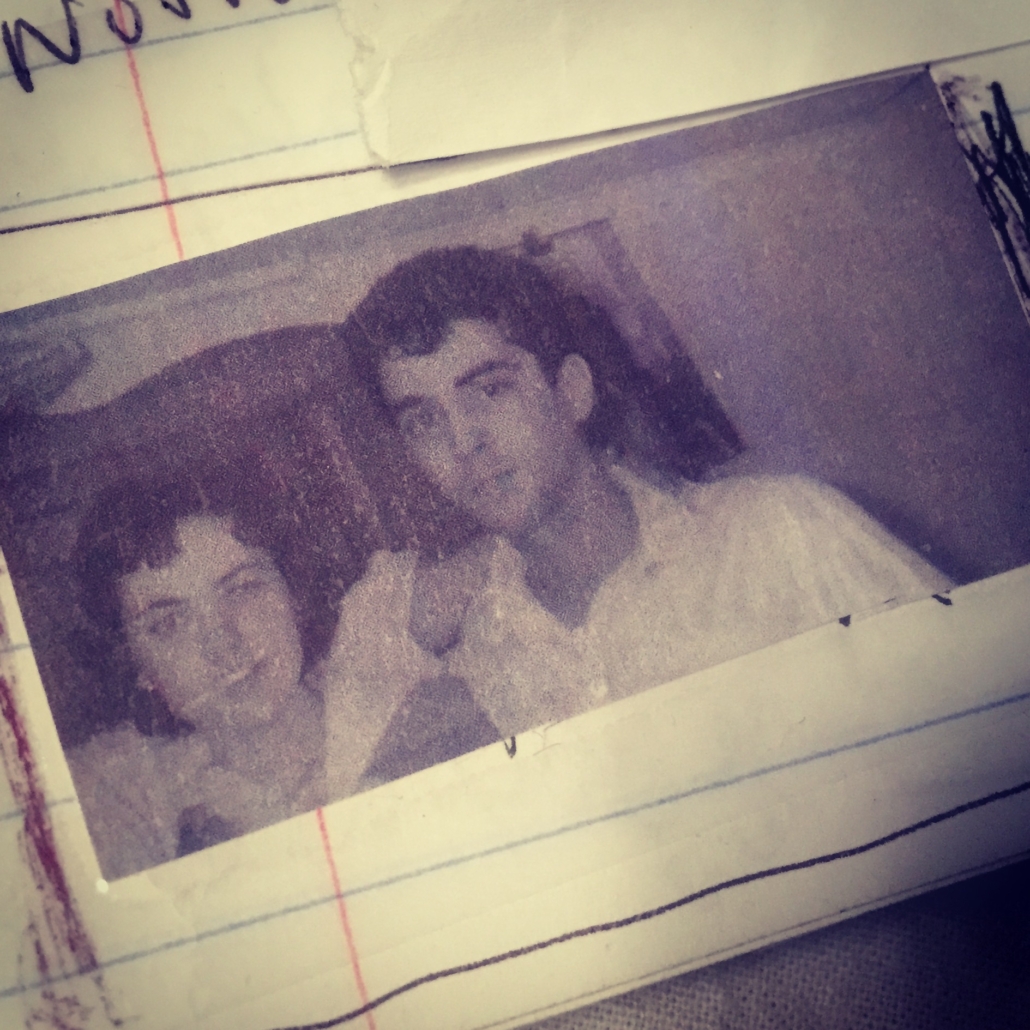

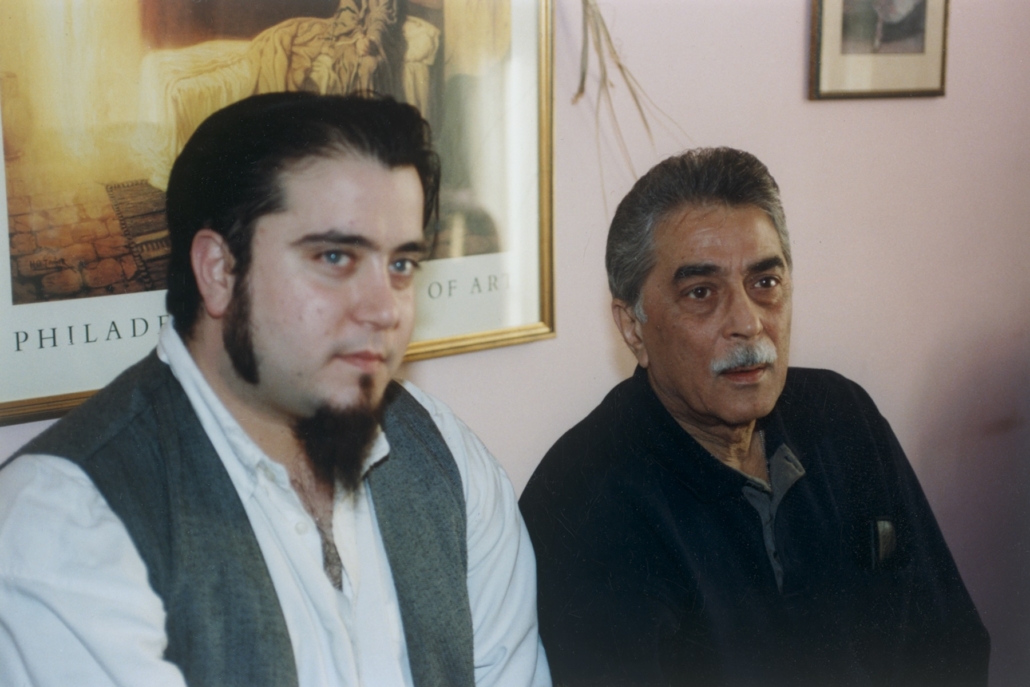

Andrew Michael Rubin was born on December 4, 1964 to Sy Rubin, a photographer, gallery director and owner of the legendary Coliseum Books; and Judy Moskowitz Rubin, a public school teacher at PS 201 in Queens and an adjunct professor at Queens College, City University.

Andy’s rich New York childhood had a lasting and profound impact on his personality. He was named in honor of Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, two of three civil rights workers murdered during the 1964 “Freedom Summer” campaign in Mississippi while attempting to register African Americans to vote. They were killed six months before he was born.

Three weeks before he died, Andy was canvassing voters in support of the Democratic Harris/ Walz campaign in the battleground states of Wisconsin and Pennsylvania.

Andy died in a hotel room in Portland, Maine on the eve of the Northeast Regional Folk Alliance Music Conference, November 22, 2024. Just a few days earlier he was promoting a show in Portland, Oregon. The last time Andy and I spoke he was riding on the train from his sister’s place in Chicago to Portland.

The coroner’s report said that Andy died of an enlarged heart. We were told by his sister Jennifer when she spoke at the funeral.

“He was so many things to so many different people,” she said. “There’s no way to capture all of who he was. As I think about him, I think about the ironies that were Andrew. He literally had the biggest heart of everyone.

“When the medical examiner said to me, he had an enlarged heart, I thought, ‘Yeah, he really did.’ Totally missing the point that she was telling me about his advanced heart disease.”

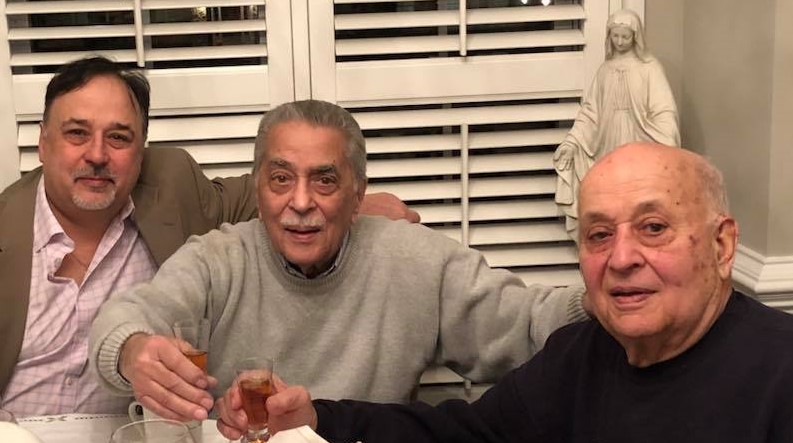

Andy was a member of multiple communities and a connector of people. This past October when the Los Angeles Dodgers and New York Yankees met in the World Series, I was contacted by a print reporter asking if I could find any old Brooklyn Dodgers fans in the City for a story. I immediately thought of Andy’s aunt Abby Tedesco, who provided the writer with the story’s most colorful quotes.

Moe Moskowitz was in ladies’ corsets. “My father managed a chain of 15 stores owned by my uncle,” Abby said. “The company was called Corsetorium. They used to say, ‘Of course it’s Corsetorium!’”

Andy’s reach was far and wide. The outpouring of affection on hearing of his passing was immense and came from people from all walks of life and all corners of the world. In the 26 years since Andy became my first friend in my adopted home city of Baltimore, I got to know many incarnations of the man.

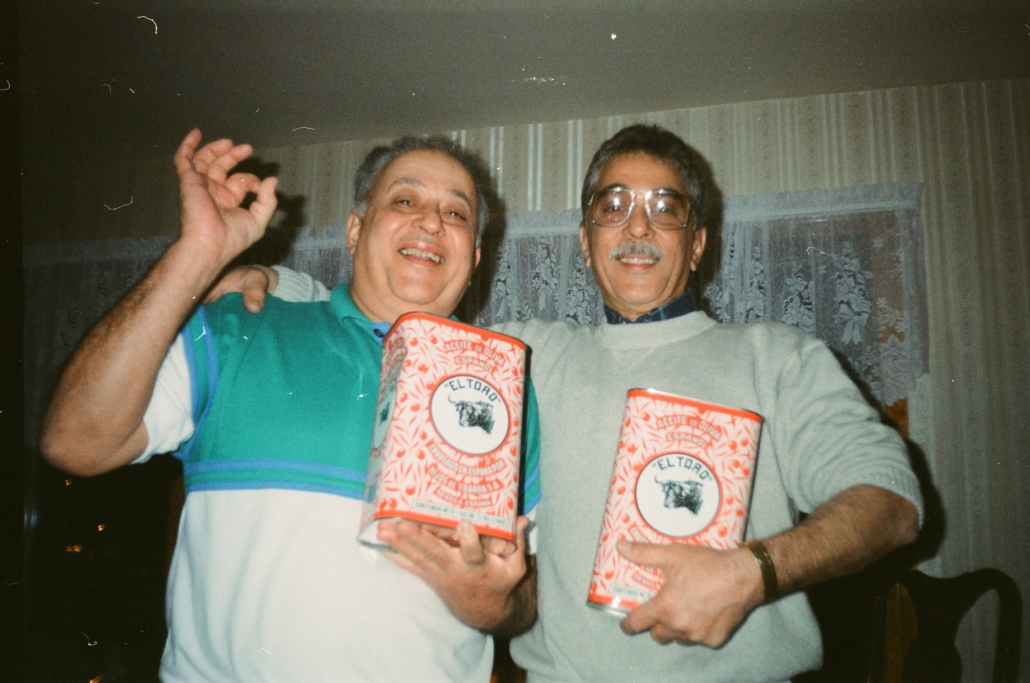

There was Andy the journalist and TV sports producer that I first met at Babe Ruth’s birthday party at Baltimore’s Havana Club in February of 1998. I wound up at the apartment Andy shared with his wife at the time, drinking a bottle of Havana Club rum his father Sy had brought back from Cuba. We became fast friends and kindred spirits tapping into our childhoods in New York rooting for the Mets. The friendship felt inevitable.

There was Andy the advocate and promoter of music and arts.

There was Andy the Vice President of Stuff for 31 Tigers Records where he produced hits for country music star Elizabeth Cook and Janet Reno’s Song of America project.

There was Andy owner of the Baltimore Chop bookstore in Pig Town and the Cyclops bookstore, art gallery and live music venue in the Station North neighborhood.

And there was always Andy the volunteer, and civil rights champion, political activist and favorite son, brother, nephew, uncle and cousin to his adoring family.

Andy’s primary motivation was improving the lives of others. He was happiest basking in the joy of his friends and family’s success. I sometimes found it difficult to live up to his expectations.

He was a conscience and sounding board and a validator of feelings. There wasn’t anything I couldn’t talk about with Andy except for our beloved New York Mets which we were always arguing about, alternating between playing the optimist and pessimist regarding the Amazins.

We were most comfortable together walking the streets of New York City, our ancestral home, like two characters in a Saul Bellow or Alfred Kazin book. We were The Odd Couple. I wanted to be Oscar but, in our relationship, I was cast as Felix, cleaning up the messes Andy sometimes left in his Mr. Magoo-like path.

In recent years Andy’s vision had begun to fail and wherever we’d meet he wouldn’t see me until well after I’d already spotted him. I started taking pictures of him on my approach chronicling how close I would have to get for him to see me.

I was with Andy at his last Mets game on October 16, 2024, an 8-0 shellacking of the Mets by the Los Angeles Dodgers in Game Three of the National League Championship at Citi Field.

“Andy walking, Andy tired, Andy take a little snooze, Tie him up when he’s fast asleep send him on a little cruise…”

– David Bowie, Andy Warhol, 1971

I used to begin our conversations by asking “Where’s Andy?”

Often, he was on a train riding the rails across the country; his favorite way to travel. He could sleep anywhere on command and in a moment’s instance. He’d crash in my car, on any sofa or hotel room floor.

An Amtrak car was pretty much his primary residence these past few decades. We’d meet up along the way in his travels and catch a ballgame in New York, or Scottsdale or Pittsburgh or just about anywhere. We’d wander the streets in the city looking for late night snacks and a place to get a good beer. He was always there for me. He was there for everyone. That’s where Andy was.

And I know by what I’ve seen these past few days that we’ll all be asking each other and never be able to forget “Where were you when you heard Andy Rubin had passed?”

For the past 30 or 40 years or more, Andy and his parents made a regular ritual of going to see folk singer Arlo Guthrie (of Alice’s Restaurant fame) perform at Carnegie Hall (conveniently located across the street from the family apartment) on Thanksgiving Day.

The night before Andy passed Alice Brock, the restaurant owner and inspiration behind the song also died from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

I’m not sure this is a coincidence.

Andy is survived by his mother Judy (Moskowitz) Rubin, his aunt Abby (Moskowitz) Tedesco, sister Jennifer (Rubin) Rothschild and her husband Gary Rothschild, as well as three nieces who agreed he was the coolest uncle ever, Danielle, Julia and Lily Rothschild, more cousins, aunts and uncles and a wide array of friends that feel like family.

Social media presence and baseball fan Rod Nelson had this to say about Andy’s passing: “The world is no longer fit for a free spirit like my friend Andy. Andy Rubin has gone to Higher Ground.”

If there’s an afterlife for the likes of Andy Rubin and Alice Brock, they play baseball 365 days a year and sing “This Land is Your Land” before each game.

Dona Bartoli Lowrimore: A daughter of Orangeville

Family and friends recall Baltimore-born “Dona” as a devoted mother, fierce advocate for women and children and a lover of all things Italian

By Rafael Alvarez / March 24, 2019

A member of the extended Brew family, Dean Bartoli Smith, suffered a loss recently, the death of his mother from cancer at the age of 76. Another Brew-er, the writer Rafael Alvarez, offers a tribute that captures her spirit – and an earlier era in Baltimore.